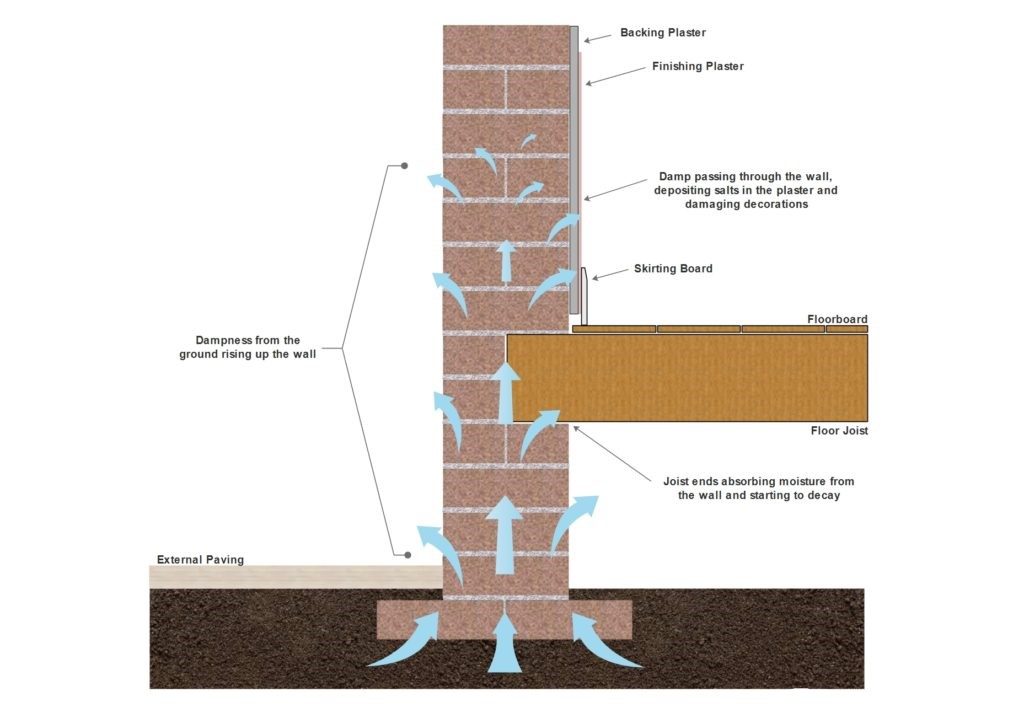

Rising damp is the upward movement of ground water through a permeable masonry wall. The water rises through the pores in the masonry via a process called capillary action and or movement. Capillary action is a process whereby water molecules are electrochemically attracted to mineral surfaces, enabling water to move vertically through pores of a certain size despite the counteractive force of gravity. It rises up the wall, often to a height of a metre or more, and usually leaves a characteristic horizontal tide mark. Below it, the wall is discoloured with general darkening and patchiness, and there may be mould growth and loose/flaky paintwork. The materials used conventionally in the construction of masonry walls are all porous to some extent so they contain a certain volume of air. The porosity is defined as the ratio of volume or air divided by the total volume, which is always less than unity. The air pockets are often connected to one another through a network of pores so liquid can pass through the material. Some values will vary depending on the particular material origin.

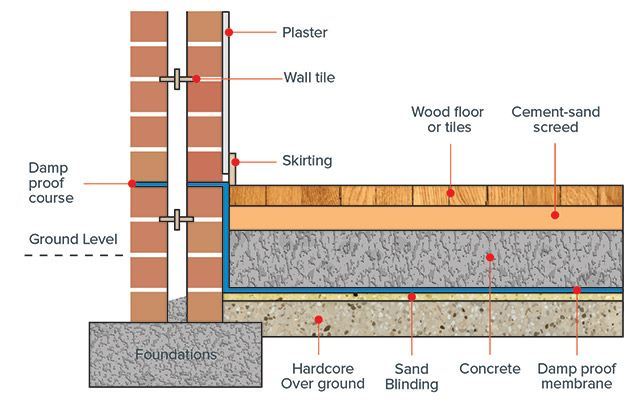

In many buildings, even with an existing damp proof course (dpc) moisture will still rise from the ground and bridge over the dpc. This scenario is called bridging and can occur when a material such as an imbalance on ground levels, exterior covering or cavity concrete mix bypasses the dpc and allows the moisture to travel past it and climb up the masonry.

Below it, the wall is discoloured with general darkening and patchiness, and there may be mould growth and loose/flaky paintwork. The materials used conventionally in the construction of masonry walls are all porous to some extent so they contain a certain volume of air. The porosity is defined as the ratio of volume or air divided by the total volume, which is always less than unity. The air pockets are often connected to one another through a network of pores so liquid can pass through the material. Some values will vary depending on the particular material origin. In many buildings, even with an existing damp proof course (dpc) moisture will still rise from the ground and bridge over the dpc. This scenario is called bridging and can occur when a material such as an imbalance on ground levels, exterior covering or cavity concrete mix bypasses the dpc and allows the moisture to travel past it and climb up the masonry.

Hygroscopic Salts

When dampness has been rising in a wall for some time, the soluble salts contained in the ground become concentrated where the water evaporates, i.e. within the plaster and within the wall itself near the apex of rise. These deposits of salts can absorb water directly from the air to such an extent that the wall can become visibly wet. This dampness effect is entirely separate from that caused by capillary rise of water and is usually referred to as “hygroscopic” dampness. This blocks the pores, reduces evaporation and raises the height of level of dampness. It should be noted that many of the salts are hygroscopic and can absorb moisture from the humid air causing damp patches in the wall. As well as a remedial treatment for Rising Damp, there also has to be a remedial treatment for the removal of the atmospheric salts within the internal materials. If the hygroscopic salt content is not properly removed then there will be reoccurring moisture problems, even after the remedial treatment of Rising Damp.

History of Damp Proof Course (DPC)

The legal requirement for a damp course was introduced in London 1875 and consequently, most older buildings were not built with damp proof courses. Slate, engineering brick or bitumen mixed with mortar were utilised in earlier construction. The architect, Thomas Worthington, described rising damp in his 1892 essay, and recommended that the damp course should disconnect the whole of the foundations from the superstructure. This preventative may consist of a double layer of thick slates bedded in cement, or of patent perforated stone-ware blocks or of three-quarters of an inch of best asphalt. It can therefore be seen that the subjects of rising damp and public health were becoming of importance in the latter part of the 19th century.

Treatment of Rising Damp

As previously mentioned, olden day construction methods consisted of mainly slate. Although some of these have a long life, it is possible for these substances to perish and allow water through. This is not the case in modern PVC damp-proof courses. In modern day construction the damp proof course installed is most likely to be a layer of PVC.

Luckily, it is possible to damp-proof most buildings without dismantling them. The main methods used today are chemical injection, mortar injection, electro-osmosis and sometimes the insertion of physical damp-proof courses or other types such as evaporative clay pots set into walls.

Chemical injection is the most suitable and cost-effective method for solid brick and cavity brick walls. The other methods are necessary for thicker stone and rubble-filled walls. They may also be suitable for breeze block walls, which are difficult to treat because of their open structure and brittle nature when drilled. The chemical method involves drilling holes into the wall at approximately 100 mm intervals and injecting a solvent or water-based chemical into the wall under pressure until the wall material is soaked with the chemical. The chemical layer then forms a solid impervious barrier and controls water rising past it. With this type of water-based cream or chemical the injection is carried out into the mortar layer between the bricks (solvent-based chemicals may be injected into the bricks themselves). This is usually at a perpendicular joint to give approximately 2 injection holes per standard brick width. This is a spacing of about 110 mm. The holes on the outside of the property are filled.